Fort Worden: A Sense of Place

Over the years I have been fortunate to attend numerous retreats and gatherings at Fort Worden, and I always look forward to return. Whether I am planning to paint or write or simply immerse myself in the company of others, time spent here is more than anything an experience of place, and this is where I will begin, before I unpack my bags, on the bluff. Here, with feet planted in dry grass and silt precipice, I can see out to the distance, across the strait and island to the sky beyond, sensing the edge of it, the vastness, the North West. It is easy in the city to forget that this part of the world is at the farthest edge of the country. This land, partially severed by water from the mass, has its own sense of being afloat, on a dome curving north, and reaching so far to the west it becomes east if you just close your eyes for a few hours and wait. It’s a vantage that feels infinitely hopeful, and one I carry with me long after I leave.

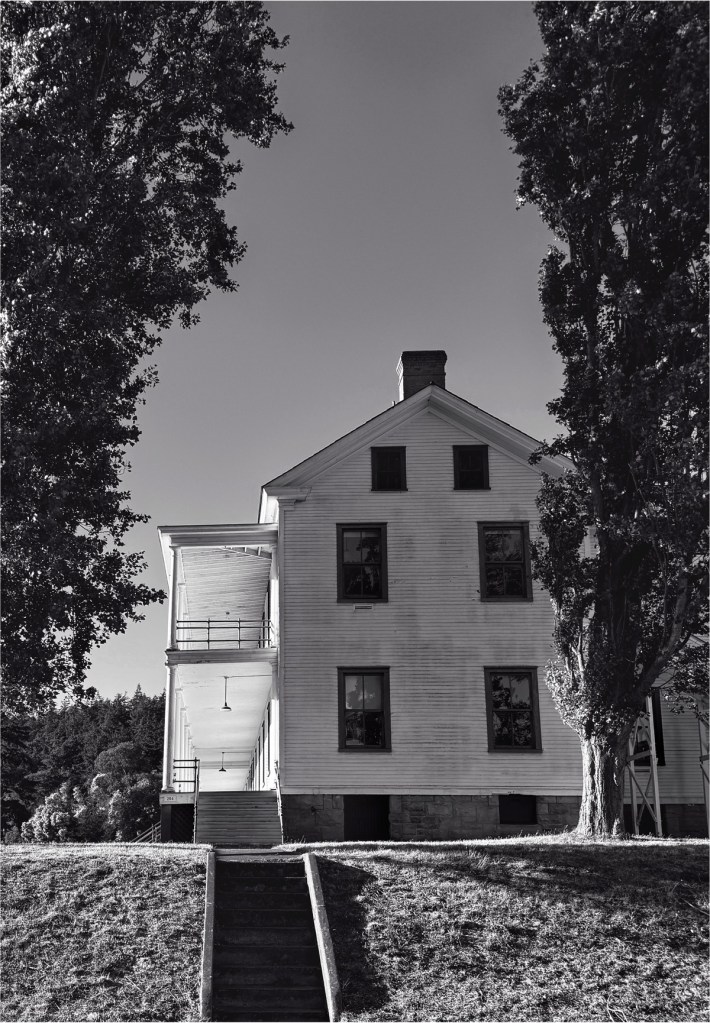

I have usually stayed here, on the bluff, in the farthest of the white barracks, always angling for a room at the top of the stairs. I have been fortunate to have a room with a view.

Perhaps my favorite moment of the day is a walk through the grounds as evening light falls on the barracks. The silence of their peeling paint and doors to nowhere, their austerity and restraint, make the bluff with its wild grasses and wind feel all the more wild. The deer wander at all hours, and if one is brooding over the predicament of a verb, or about meaning, or one’s own place in the sentence, their gaze is a welcome benediction.

Notes on the Port Townsend Writers Conference

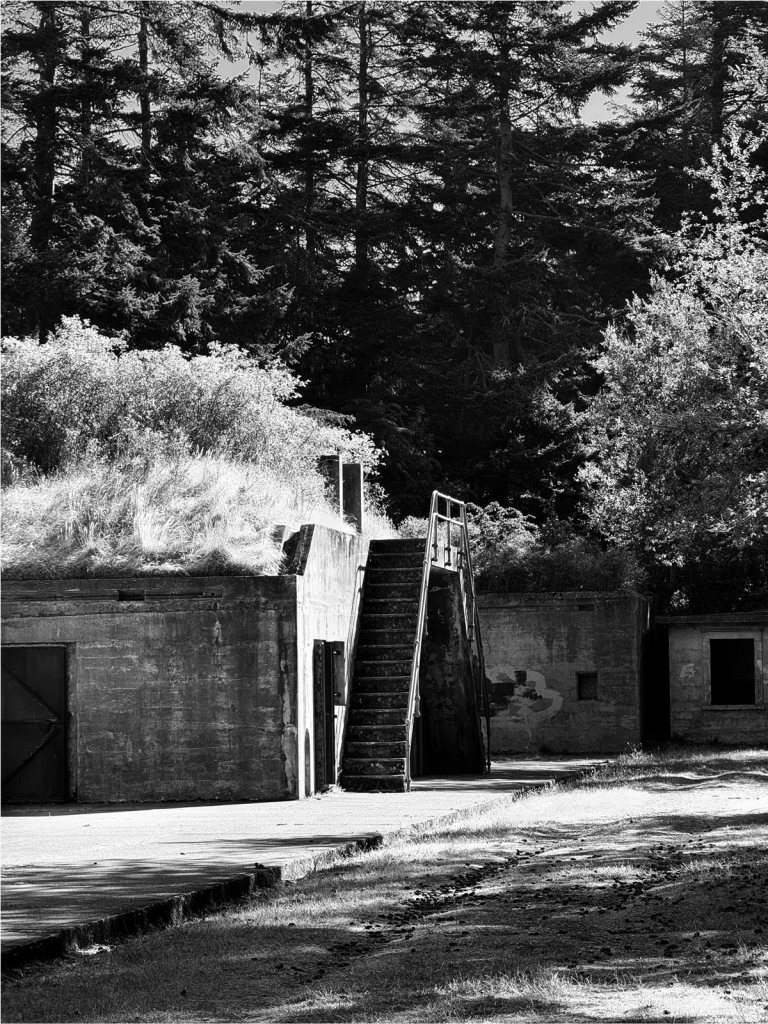

In my ongoing campaign to make life longer I have discovered two strategies: travel to a foreign land, and talk to people you don’t know. Do this and each day will seem a week long; one week at a conference can add a month to your life. Fort Worden, with its mess hall, officers’ quarters, theaters, its abandoned forts in exquisite decay and all the sprawling lawn between, is its own private country. Then there are 100-150 people to meet and names to learn and immediately forget— though never the conversations. To get the most out of the conference you should stay on site, and sit at the big round tables and eat the commissary food, no matter how awful.

If you go off campus you may have a much better sandwich, but you will miss things like #ThePoetFacePalm. As on the first morning, when I sat down and began a rousing shouted cross-table conversation about Tony Hoagland, and which poet is better, Mary Oliver or Jane Hirschfield, moving on from there to dissing and dishing on all the greats with great authority, only to find out later that the person I was having this disputatious argument with was a Known Poet and teacher at the conference. I have often thought that social media is the great equalizer, but perhaps the greater equalizer is a round table among other round tables in a cafeteria. If you carry your nutritious meals with you in little bags and eat by yourself in contemplative solitude, you do miss the comeuppance moments, which can be entertaining.

The demographics of this conference, tilted firmly to the over 50’s, could be daunting to any young person, although the old suffer as well, as there is no shortage of ways to compete with others and emerge from the battle garroted, tossed onto the heap of irrelevance. My informal survey indicated that anyone under 40, particularly if they had tattoos, was writing a novel that takes place in the future. Anyone over 40 was either telling fiction in disguise about their tortured childhood or had mastered actual fiction and was at work on a trilogy set in the 1700’s. Everyone seriously over 70 was deep in the sorting of recollection, end of life and regrets: people over 70 have seen the future, and they would just as soon put if off as long as possible.

Perhaps the best way to capture the emotional tenor of the week is a visit to the commissary.

Overheard

They say everyone reading manuscripts at the literary journals is young, probably a 25-year-old graduate student.

Exactly. They don’t want to hear about losing your mother to dementia or writing a will or what it is like to be the last one standing in your family, they want young stories.

I killed my father.

Wait— you killed your father or your father was killed by the character? You don’t mean really? Is this in the future or the past?

I hate the future.

This food, I just can’t. I just can’t. It’s just so so dry.

But the curry the first day!

Yes the curry. That was 48 hours ago.

But there was that curry on the first day and it was good.

(The Curry on the First Day was discussed for seven days.)

I heard you need a PhD now to be a TA. I have a Masters and I cannot get a job. I’m 26. I’ve won awards! I’m published. My best work is about working at 7-11 but I’m $120,000 in debt. I can’t go back to that. . .

So what’s the best method of assisted suicide?

Oh, it’s definitely starvation. It’s safe, it’s legal, we did it with my aunt and it was easy.

No, it’s not easy. Don’t ever think it’s easy. Watching someone die of starvation can scar you for life.

She’s wrong people, you just need to use enough morphine.

So…what again, is “World Building?”

Are you also writing about trans vampires on other planets?

Why do you ask?

So what do you think about the future? For young poets like us, can you give us any advice? I mean, you all have so much more experience.

Are you referring to your one wild and precious life? Follow your bliss. You will never regret it.

Don’t listen to him girls, you will be in debt for life and you will never own anything—you need a solid financial foundation.

She’s right. Times are different. Rent is out of sight, it’s impossible to save money, you’ll malinger in the underclass forever without a real job to back you up.

Get that PhD. Teaching is a real job.

I’m a poet and I followed my bliss but it ended up that a job in advertising was also my bliss so I made a lot of money. A lot of the great poets were in advertising. Or insurance, you know.

I used to think I could give young people advice but now that AI is here I am speechless. I live in dread and I do not know what we are all going to do — Maybe bot poetry will be where it’s at by Tuesday. Then there’s no point in getting a degree, much less writing.

Sooo negative! Focus on people. Connect: with EVERYONE. In this age social skills have never been more important and they win over the machine every time.

Lastly:

This is highschool, right? Paralyzed. If I sit alone will anyone join me and if I sit at one of those tables will anyone ask my name.

It’s on your badge, don’t worry.

It’s highschool but we’re adults and we’ve all been in therapy. I can do this. . .

See what you miss if you eat in your room?

In the Classroom

In between scenes from The Commissary, there were lessons in formal storycraft. Every morning I attended a three-hour class with an ongoing cohort, and in the afternoon I could choose from an array of short workshops, with alluring titles like The Art of Juxtaposition, The List as Architecture and Informant Ghosts of History.

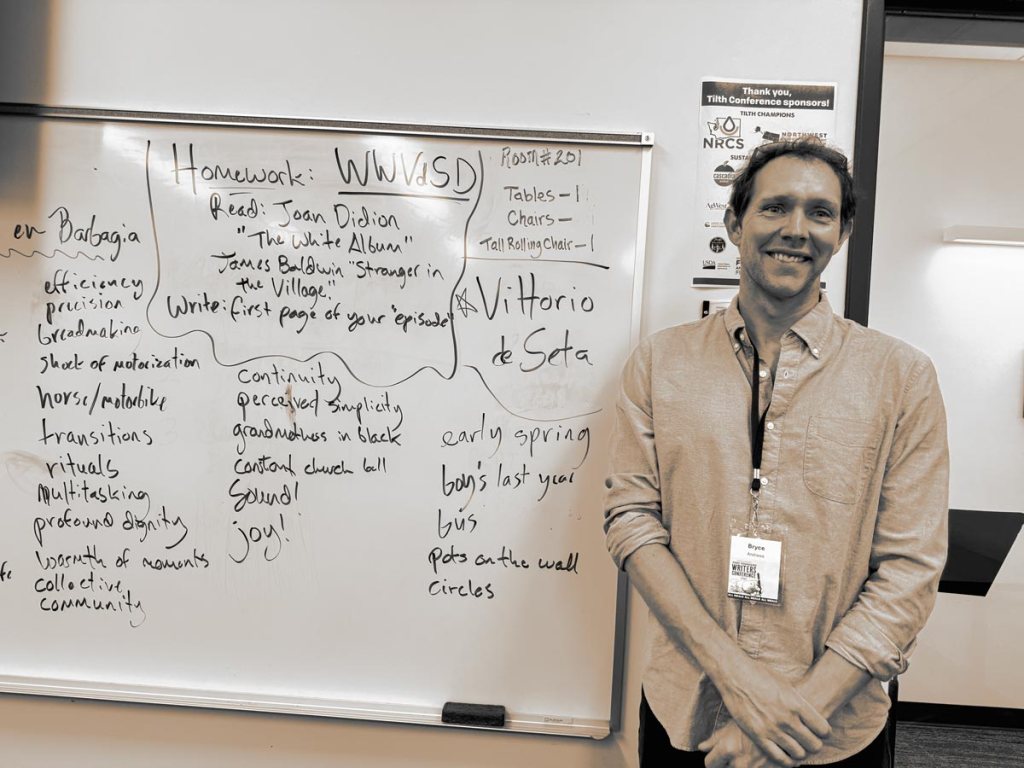

I signed up for the conference at the last minute and had little choice in morning instructors. I chose Bryce Andrews, who I had never read, based on the title of his workshop, “Awful, Beautiful “I” (Narrative Nonfiction)” — a title that in just five words gets to the heart of the dilemma:

This workshop is about telling stories from the raw materials of life, in the first person. In other words, God help us, it is about memoir. Perhaps you have a complicated relationship with the genre and its inevitable pronoun, considering one the province and the other a hallmark of navel-gazing egotism. You’re not completely wrong.

The workshop, however, pursues a breed of memoir that looks through, as much as into, the author’s life. It is about finding an essential story in the run of days and recognizing one’s own experience as a lens that can be turned, unflinchingly and searingly, on the larger world. Memoir as commentary, warning, revelation, or antidote.

My experience was completely wonderful. Bryce is a gifted and innovative teacher. He pushed us beyond our usual thinking with challenging, unexpected material and multiple ways of looking at narrative. I am deeply grateful for the writers he introduced us to, and I am avidly reading new authors daily, furiously marking up the margins of William Kittredge and John D’Agata. Any class is as much about one’s peers as the instructor, and I was fortunate to land in a deeply thoughtful and empathetic group, with a fascinating range of life experience. I have never been in graduate school, but it felt like what that should be. In my own writing I was startled to find that an idea I’ve been thinking about for years as a series of poems might be a completely different form, and at the conference I completed two chapters of what appears to be a book. Whether it turns out to be conventional narrative or something more adventurous will take some time.

Standing Up and Speaking in Public

I have always had crippling stage fright, perhaps triggered by my performance, standing on a folding chair in the sixth grade, of Maurice Sendak’s Pierre: A Cautionary Tale in Five Chapters and a Prologue. On my fifth shouted affirmation of I DON’T CARE! The chair collapsed. I have been trembling and sweating in public ever since. This is the kind of stage fright that is whole-body, uncontrollable, and instantaneous. One moment I am carrying on with friends telling a perhaps-tall tale with absolute confidence, and the next I am in front of a microphone with sweat dripping into my shoes, unable to get my vocal chords to work.

This has become so very tiresome. I seized the many opportunities to read in public, in class, afterwards at the formal open mic and the later dormitory readings on the couch. I am deeply grateful for the hugs and the encouragement, and I can say my voice now comes out as scheduled 100% of the time, even if it may take a minute for the shaking to stop. Reading work aloud is also an important part of the writing process. Words compose differently when spoken, and the interplay between writing and speaking greatly improves my work. More and more I begin my pieces by recording them, using the Notes app on my phone, and then editing them in Word.

The culture of the Centrum gatherings was warm and welcoming, and many of the readings were unforgettable. If my favorite place to talk to strangers is on an airplane just before the person next to me falls asleep, second best is on a chair in the half light of a spoken word performance. How few places we have, outside of a bar or a therapist’s couch, to share unexpected vulnerabilities. As pandemic unwinds its fist and the world moves off Zoom, these gatherings have also grown in number in my own city, Seattle, and across the country, and it is heartening to see.

Gallagher-Lilley and Indigenous Writers Fellowship Program

The last night of the conference began with a performance and celebration at the McCurdy Pavilion. Participants in the Gallagher-Lilley and Indigenous Writers Fellowship Program took center stage, with moving and skillful readings from indigenous poets and writers and particularly strong performances from young poets, many of whom had impressed me during the week with their seriousness of purpose, clarity and talent. As the new Gilded Age divides us ever more deeply along lines of class, those lines have also come to represent generational divide. I worked hard as an entrepreneur and artist for decades for what comforts I have, but I am not confident that hard work will allow younger generations to acquire more than a fraction of the security and assets of the middle class today. A week away to write and study is a rare opportunity few young people can afford.

I know there are many worthy causes to give to, but I hope conference participants, writers, readers and supporters of the arts will consider donating to the Fellows fund, generously started with seed money from Tess Gallagher. You can go here to donate, (and be sure to scroll down and write “Gallagher-Lilley and Indigenous Writers Fellowship” in the “Comments and special instructions.”)

Before I went to bed I attended two more readings, hanging on to every word and saying last goodbyes to new friends, finally collapsing in my bed around midnight. The next morning I left at dawn to have espresso exactly where I started 7 days earlier, at a café in Port Townsend. There I stared out the window, read, wrote, and caught a ferry to Driftwood Beach on Whidbey Island, where I settled in against a long silver tree and listened only to the wind. I have been writing daily ever since.

Coda: The Fort

Over the years I have taken hundreds of photographs of the ruins at Fort Worden. But each time I think it’s all been said, light tells a different story. Here, a small selection of photographs from a morning walk above the Bluff.

Photographs and writing (except for course catalog description) © Iskra Johnson 2025 and may not be reproduced without permission.

Iskra Johnson is an artist, writer and activist involved in environmental preservation and affordable housing. You can find her visual art and photography at her website, Iskra Fine Art.

Leave a comment