Gathering in person may be the most important resistance

In March of this year it began to feel to me uneasily like spring of 2020 when the news feed descended into darkness, lockdowns loomed, and pandemic life meant a life of surrogates, (to which I fear, we became accustomed and all too fond.) Everything that once involved face to face contact became remote, untouchable, and experienced through a glowing lcd screen or a gelatinous barrier of hand sanitizer. It was also, for those with money, appeaallingly convenient. Just order on app, and everything your heart desired came to your door without friction, the delivery mark-up paid for by the irrationally exuberant stock market.

I manned the barricades of my mental health in 2020 by collecting vintage newspapers from Ebay. Instead of turning to the New York Times mortality reports I turned the crumbling pages of 1915’s Musical America, relishing morning toast with news of the consummations and rivalries of contraltos and bassists in American drawing rooms and conservatories in the middle of WW1. The want ads were a revelation. Even war has its upsides, like discounts on cello lessons, provided by desperate (and famous in Moldavia) immigrant musicians.

I loved reading between the lines: “Mr. William Stansfield, marshalling his singers for the pretentious religious works he means to present this winter. . .” And what exactly went on in the Christ Church cloakroom before soprano soloist Ethel Whelan and Mr. Jay Edwards Jr,. the bassist in the same church, tied the knot? It was not just the endearing pettiness and gossip that appealed to me, but the paperness. I could touch the news, and in running my hands across the fragile newsprint and blurred gray photos feel connected to history in the middle of a time that threatened to break history itself.

Now, five years later, I scroll the screen of my phone and can find no escape from the news of the daily deconstruction of the United States. How had I taken it all for granted? Safe water, clean air, hospitals, medical research, Social Security, National Parks, the rule of law, a stable stock market, the dollar itself – all at risk. I find myself fighting despair and helplessness, often paralyzed in an obsessive trance, broken only by the question “what can I do?” I write letters to my Senators and Representatives every week. I sign petitions. I call the White House. I subscribe to the Wall Street Journal and National Review to see how the conservative mind thinks and leave comments linking to factual rather than alternative truths (undocumented immigrants, for instance, are not bankrupting Social Security, and in fact they pay an estimated $25 billion into Social Security each year.) I rally my friends on Facebook to write to the AARP to save Social Security. And in the middle of it all what I really need is people in my living room.

Perhaps the most memorable moment of the last few months was on a day in February when I sat next to a woman reading a book at the Starbucks on Highway 99. Because book reading is so rare I felt excused for interrupting, and ask her what the book was. She said, in an accent I had never heard, On Tyranny:Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century. “Where are you from?” I asked, and she pointed to her t-shirt, which had a map of Moldavia – a country so small and uncertain it barely fits on maps today. What followed was an education in Russian and Ottoman conquest, and a sense of connection affirmed when my new friend left and unexpectedly returned to hand me a book written by her daughter, Gabriela “la Moldava” Condrea. Gabriela had spent a year studying tango all through Latin America, and her book speaks very much to what we need in this moment:

“Tango is a representation of how we relate to each other. It’s about the connection we cultivate with those who surround us, with our partner, with ourselves. It’s about the way we interlace and intertwine with one another. We are because we feel, because we form invisible ties and timeless links to one another. Life is about the energy we share – a gaze, an embrace, a fleeting exchange of irreplicable moments – so subtle yet so powerful; life is about the connection.”

How do we cultivate connection in a modern culture built for technological distance? And more pointedly, how do we connect in a city like Seattle that seems to have embraced pandemic reserve as a welcome, and permanent, social code? I grew up in the hotbed of leftist politics in Seattle. We had no internet, no email, no cell phones or texts; there was a mimeograph machine in the basement. There were weekly parties to make protest signs. I long for that lost sense of “us” and the shared purpose shouted and argued over countless spaghetti dinners in the homes of the old, new and middle left of the 1950’s and ‘60’s. Back then you could shout at someone, accuse them of being a Trotskyite, and still keep drinking wine together – the more shouting the better. Today’s discourse has devolved into an unforgiving tightrope across schisms, made ever more volatile by the adversarial design of social media and today’s treacherous parlor – the comment section.

In response to a (possibly desperate) midnight letter, a dozen people came to my living room last weekend. I learned this week that these gatherings are happening all over the city –it is not just me who knows I can’t do this alone with my phone. Perhaps it was the contagion of the protests of April 5th, perhaps the spirt of Seder, or the potluck mish mash of lasagna and haroset, but the room felt alive with hope, and the kind of conversation I urgently miss. I asked the question that had been most on my mind: what makes you feel American, if you ever did? And what was that moment?

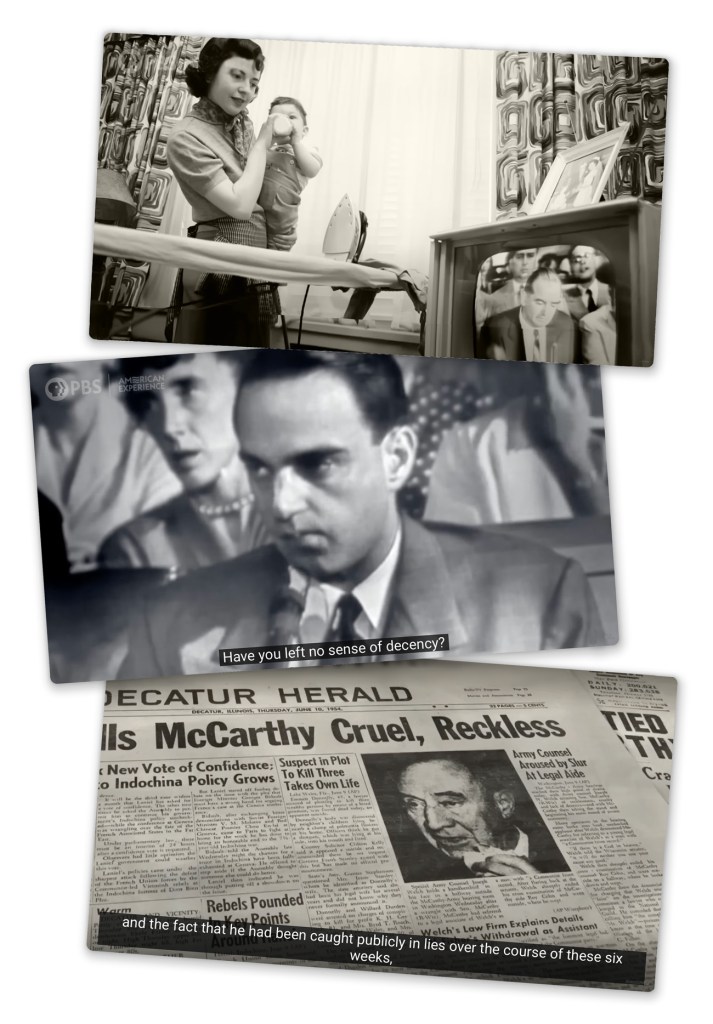

This question is one to which I have given a great deal of thought. For people on the Left, educated in suspicion of all things “patriotic”, the idea of identifying as an “American” can be unnerving. The discussion that followed ranged from personal anecdote to the broader values of civic life, histories of protest, and what is lost when we stop having a shared sense of what is true. How, as someone asked on social media the other day, did the McCarthy Era end? It ended because everyone in America saw the hearings on television, on networks they had no reason to disbelieve. And when they saw the bullying in the courtroom (which would in today’s eyes seem mild) they collectively said, no more. How, in this Orwellian age, do we find any shared belief with others, when every person is watching a different channel?

Three main themes emerged in our discussion: the need for talking with people across political divides, a revival of civics, and the search for effective paths for action. All of these come together for me in the history of the American Chautauqua. In the 1970’s when I was an earnest student of calligraphy, a bible of the time was the remarkable, entirely handwritten Recollections of the Lyceum & Chautauqua Circuits, by the calligrapher Raymond DaBoll and his wife Irene Briggs. The Chautauqua Movement, called by Theodore Roosevelt “The most American thing in America” began in 1874. For over 50 years the Chautauqua Circuit brought communities together through programs of music, art, performance, religion and civic education.

What would this look like today? I think it begins with a hot dish, poetry, reading aloud, banjos, pianos, a bit of 1960’s irreverence and a love of learning. A few of the organizations at work restoring civics to our communities include The League of Women Voters, Civics for All and the National Civics League. I know my own knowledge is sketchy; I need to install a Bill of Rights shower curtain and Constitutional placemats to remind myself of history until I know it by heart – and I should not have to get a latin primer to translate habeas corpus.

One thing I love about the words “New Chautauqua” is that it is also the name of one of Pat Metheny’s finest albums. As in much of his best work, here he weaves together pastoral melody, Americana, reverie and a cinematic sense of landscape. It is music that takes you to a place you can psychically live in. To survive and thrive in this tumultuous time we need art as much as politics, opinion and poetry. I hope readers will send me your thoughts on Chautauqua here in comments or in email. Are you gathering people together? What does the New Chautauqua look like to you?

To read more about how we reclaim patriotism and build community, along with essays on art, culture, politics and history follow me here and subscribe to The Iskra Journal.

Leave a comment